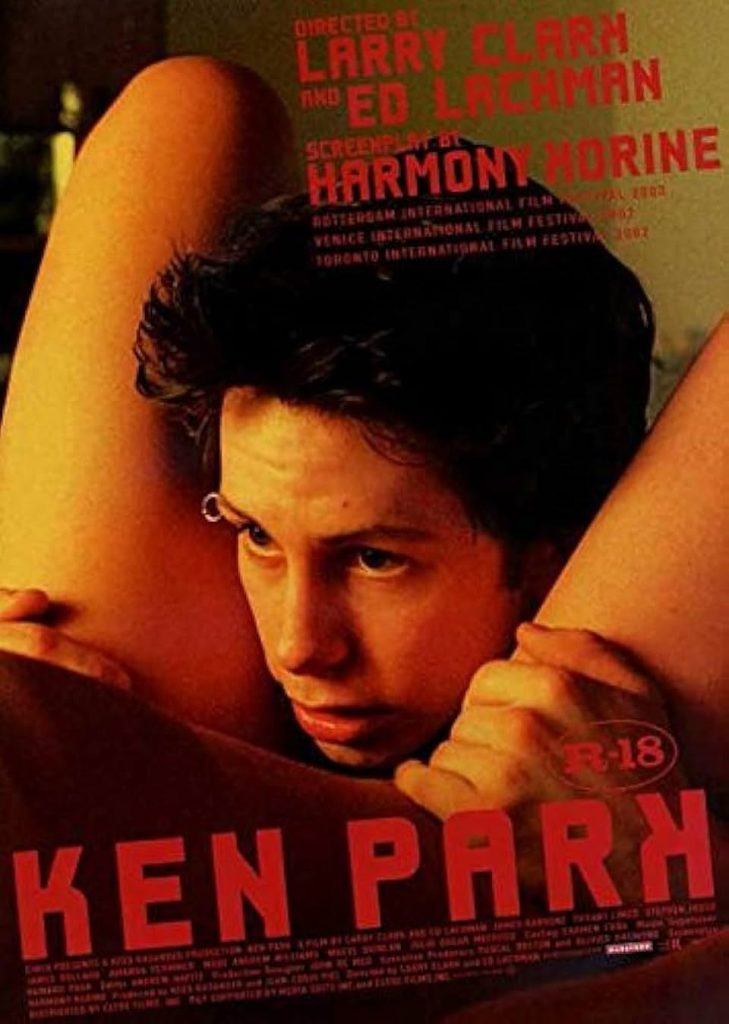

Movie name: Ken Park (2002)

A Review of Ken Park (2002): A Provocative Descent into Suburban Disillusionment

Ken Park, directed by Larry Clark and Edward Lachman, is a polarizing cinematic work that delves into the raw, often uncomfortable underbelly of suburban American youth culture. Released in 2002, the film follows the lives of a group of teenagers in Visalia, California, as they navigate dysfunctional families, fractured relationships, and their own burgeoning identities. Known for its unflinching portrayal of adolescent struggles, Ken Park is both a continuation of Clark’s signature style—seen in films like Kids (1995) and Bully (2001)—and a collaboration with cinematographer Edward Lachman, whose visual artistry amplifies the film’s gritty realism. This review explores the film’s thematic depth, character dynamics, stylistic choices, and its place within Clark’s oeuvre, while addressing its controversial reception and cultural significance.

Narrative Structure and Thematic Core

At its core, Ken Park is an ensemble drama that weaves together the stories of four teenagers—Shawn, Claude, Peaches, and Tate—along with a fifth character, Ken Park, whose brief but pivotal presence bookends the film. The narrative is non-linear in its emotional progression, though it unfolds chronologically, with each character’s arc intersecting loosely through shared spaces and social circles. The film’s structure mirrors the chaotic, fragmented lives of its protagonists, eschewing traditional plot resolution for a more episodic, vignette-like approach. This choice amplifies the sense of aimlessness that permeates the characters’ existences, reflecting the ennui of suburban adolescence.

Thematically, Ken Park is a meditation on alienation, the breakdown of familial bonds, and the search for meaning in a world that feels both stifling and indifferent. The film probes the tension between freedom and entrapment, particularly through the lens of youth caught between childhood dependence and adult responsibility. Each character grapples with their environment in distinct ways: Shawn seeks connection through forbidden relationships, Claude battles an abusive father, Peaches navigates her father’s oppressive religiosity, and Tate spirals into nihilistic rage. Ken Park himself serves as a spectral figure, his story revealed in fragments that frame the film’s exploration of despair and fleeting moments of transcendence.

The film’s refusal to moralize or provide clear answers is both its strength and its point of contention. Clark and Lachman present their characters’ lives with a raw, almost anthropological lens, inviting viewers to witness rather than judge. This approach, however, has led to accusations of sensationalism, as the film’s graphic depictions of violence, substance use, and intimate relationships push boundaries that many find unsettling. Yet, beneath its provocative surface, Ken Park is a deeply human story, one that asks difficult questions about the societal structures that shape young lives.

Character Analysis: Portraits of Disconnection

The strength of Ken Park lies in its vivid, flawed characters, portrayed by a cast of relatively unknown actors who bring authenticity to their roles. Each teenager represents a facet of the film’s broader commentary on suburban disillusionment, and their interactions with family and peers reveal the complexities of their inner worlds.

-

Shawn: Played by James Bullard, Shawn is the film’s quiet observer, a skateboarder who drifts through life with a mix of curiosity and detachment. His relationship with an older figure in his life complicates his search for stability, highlighting the blurred lines between affection and exploitation. Shawn’s arc is understated but poignant, as he grapples with loyalty to his family while seeking escape through fleeting connections. Bullard’s naturalistic performance captures Shawn’s vulnerability, making him a relatable entry point for viewers.

-

Claude: Stephen Jasso’s portrayal of Claude is one of the film’s most heartbreaking. A sensitive, athletic teen, Claude endures relentless verbal and physical abuse from his father, Curtis, a volatile alcoholic. The dynamic between Claude and Curtis is a microcosm of toxic masculinity, with Claude’s attempts to please his father met with cruelty. Claude’s skateboard becomes a symbol of rebellion and release, offering him a temporary reprieve from his oppressive home life. Jasso imbues Claude with a quiet resilience, making his moments of defiance both cathartic and tragic.

-

Peaches: Tiffany Limos delivers a standout performance as Peaches, a young woman trapped under her father’s suffocating control. After losing her mother, Peaches becomes the object of her father’s obsessive protectiveness, which manifests in strict religious rules and invasive oversight. Her rebellion takes the form of secret relationships, which she uses to reclaim agency over her life. Limos portrays Peaches with a delicate balance of defiance and fragility, highlighting the tension between her desire for freedom and her fear of losing her father’s love.

-

Tate: James Ransone’s Tate is the film’s most volatile character, a ticking time bomb of repressed anger and nihilistic impulses. Living with his grandparents, Tate’s isolation fuels his descent into disturbing behavior, culminating in acts of violence that shock even within the film’s already intense framework. Ransone’s performance is electrifying, capturing Tate’s manic energy and underlying pain. While Tate’s actions are difficult to watch, they underscore the film’s thesis about the consequences of neglect and emotional repression.

-

Ken Park: Though his screen time is limited, Ken Park (Adam Chubbuck) is the film’s emotional anchor. His story, revealed through fragmented flashbacks, sets the tone for the film’s exploration of despair and fleeting moments of connection. Ken’s quiet demeanor and tragic arc serve as a haunting reminder of the fragility of youth, making his presence linger over the entire narrative.

The ensemble nature of Ken Park allows for a kaleidoscopic view of its characters’ lives, with each actor delivering a performance that feels raw and unfiltered. The casting of non-professional or lesser-known actors enhances the film’s documentary-like quality, blurring the line between fiction and reality.

Cinematography and Visual Style

Edward Lachman’s cinematography is a defining element of Ken Park, elevating it beyond mere provocation into the realm of visual poetry. Lachman, known for his work on films like Far from Heaven and Carol, brings a painterly sensibility to the film’s gritty subject matter. Shot on 35mm film, Ken Park has a tactile, lived-in quality, with warm, saturated colors that contrast sharply with the bleakness of its narrative. The suburban landscapes of Visalia—strip malls, skate parks, and cookie-cutter houses—become characters in their own right, their banality amplifying the characters’ sense of entrapment.

Lachman’s camera is both intimate and voyeuristic, often lingering on characters in moments of vulnerability or rebellion. Handheld shots dominate the film, creating a sense of immediacy and immersion, while carefully composed wide shots underscore the isolation of the suburban sprawl. The use of natural light enhances the film’s realism, with scenes bathed in the golden glow of California sunsets or the harsh fluorescence of domestic interiors. These visual choices reinforce the film’s thematic tension between beauty and decay, freedom and confinement.

The skateboarding sequences, a recurring motif, are particularly striking. Lachman captures the fluidity and grace of the characters’ movements, using slow-motion and dynamic angles to evoke a sense of fleeting liberation. These moments stand in stark contrast to the claustrophobic domestic scenes, where tight framing and shallow depth of field trap characters within their environments. The interplay between these visual modes underscores the film’s exploration of escape and entrapment, making the cinematography a narrative tool as much as an aesthetic one.

Soundtrack and Sound Design

The soundtrack of Ken Park is an eclectic mix of punk, alternative rock, and ambient music, reflecting the rebellious spirit of its characters. Bands like Rancid, The Shins, and Gary Stewart contribute tracks that pulse with raw energy, grounding the film in the early 2000s youth culture. The music often serves as a counterpoint to the characters’ inner turmoil, with upbeat tempos clashing against scenes of emotional or physical conflict. This dissonance mirrors the film’s broader thematic tension between surface-level normalcy and underlying dysfunction.

Sound design plays a subtler but equally important role. The ambient sounds of suburban life—lawnmowers, distant traffic, the clatter of skateboards—create a sonic backdrop that feels both familiar and oppressive. In moments of heightened emotion, the soundscape becomes sparse, allowing the weight of silence to amplify the characters’ isolation. The interplay between music, ambient sound, and silence enhances the film’s immersive quality, drawing viewers deeper into its world.

Controversy and Reception

Upon its release, Ken Park sparked intense controversy for its explicit content and unflinching portrayal of adolescent life. The film faced censorship in several countries, including Australia, where it was banned outright, and it struggled to find distribution in the United States due to its provocative nature. Critics were sharply divided: some praised the film’s raw honesty and visual artistry, while others condemned it as exploitative or gratuitous. Roger Ebert, for instance, acknowledged Clark’s talent but questioned the film’s moral framework, while others, like Manohla Dargis, defended its uncompromising vision as a necessary provocation.

The controversy surrounding Ken Park stems from its refusal to sanitize or romanticize its subject matter. Clark and Lachman present their characters’ lives with a stark realism that challenges viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about youth, family, and society. For some, this approach is a bold artistic statement; for others, it crosses ethical lines. The debate over the film’s merit reflects broader questions about the role of art in depicting difficult subjects, making Ken Park a lightning rod for discussions about censorship, representation, and artistic intent.

Cultural Context and Legacy

Ken Park emerged at a time when American independent cinema was grappling with the complexities of youth culture. Following the success of Clark’s Kids, which shocked audiences with its portrayal of urban teens, Ken Park shifted the focus to the suburbs, exposing the dysfunction lurking beneath the façade of middle-class normalcy. The film can be seen as part of a broader wave of early 2000s cinema—films like Donnie Darko, Thirteen, and American Beauty—that explored the darker side of suburban life and the alienation of youth.

In the context of Clark’s filmography, Ken Park represents both a culmination and an evolution of his preoccupations. Like Kids and Bully, it examines the raw edges of adolescence, but it does so with a more lyrical, almost elegiac tone, thanks in part to Lachman’s contributions. The film’s focus on family dynamics also sets it apart, offering a more nuanced exploration of how parental dysfunction shapes young lives. While less commercially successful than Kids, Ken Park has garnered a cult following among cinephiles who admire its boldness and emotional depth.

The film’s legacy is complex. It remains a touchstone for discussions about the ethics of depicting youth onscreen, particularly in relation to controversial subject matter. Its influence can be seen in later works that tackle similar themes, such as Gregg Araki’s Mysterious Skin or Andrea Arnold’s Fish Tank, which balance raw realism with empathetic storytelling. For better or worse, Ken Park is a film that refuses to be ignored, demanding that viewers engage with its uncomfortable truths.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Ken Park is not without flaws. Its episodic structure, while thematically resonant, can feel disjointed, with some character arcs receiving more attention than others. The film’s unrelenting intensity may alienate viewers seeking nuance or resolution, and its provocative elements risk overshadowing its deeper insights. Additionally, the lack of a clear narrative payoff may frustrate those accustomed to conventional storytelling.

Yet, these weaknesses are arguably integral to the film’s impact. The lack of resolution mirrors the characters’ own sense of aimlessness, while the provocative content forces viewers to confront the realities of its world. The film’s strengths—its vivid characters, stunning cinematography, and unflinching honesty—far outweigh its shortcomings, making it a powerful, if challenging, cinematic experience.

Conclusion

Ken Park is a film that defies easy categorization. It is at once a raw portrait of adolescent disillusionment, a visually arresting work of art, and a provocative challenge to societal norms. Larry Clark and Edward Lachman have crafted a film that is as beautiful as it is unsettling, using the lens of suburban youth to explore universal themes of alienation, family, and the search for meaning. While its controversial elements have sparked debate, they also underscore the film’s commitment to honesty, refusing to shy away from the messiness of human experience.

For those willing to engage with its intensity, Ken Park offers a profound meditation on the fragility of youth and the societal forces that shape it. It is not a film for everyone, but for those who resonate with its raw energy and unflinching vision, it is an unforgettable journey into the heart of suburban disillusionment. As a testament to the power of independent cinema, Ken Park remains a bold, divisive, and enduring work that continues to provoke, challenge, and inspire.